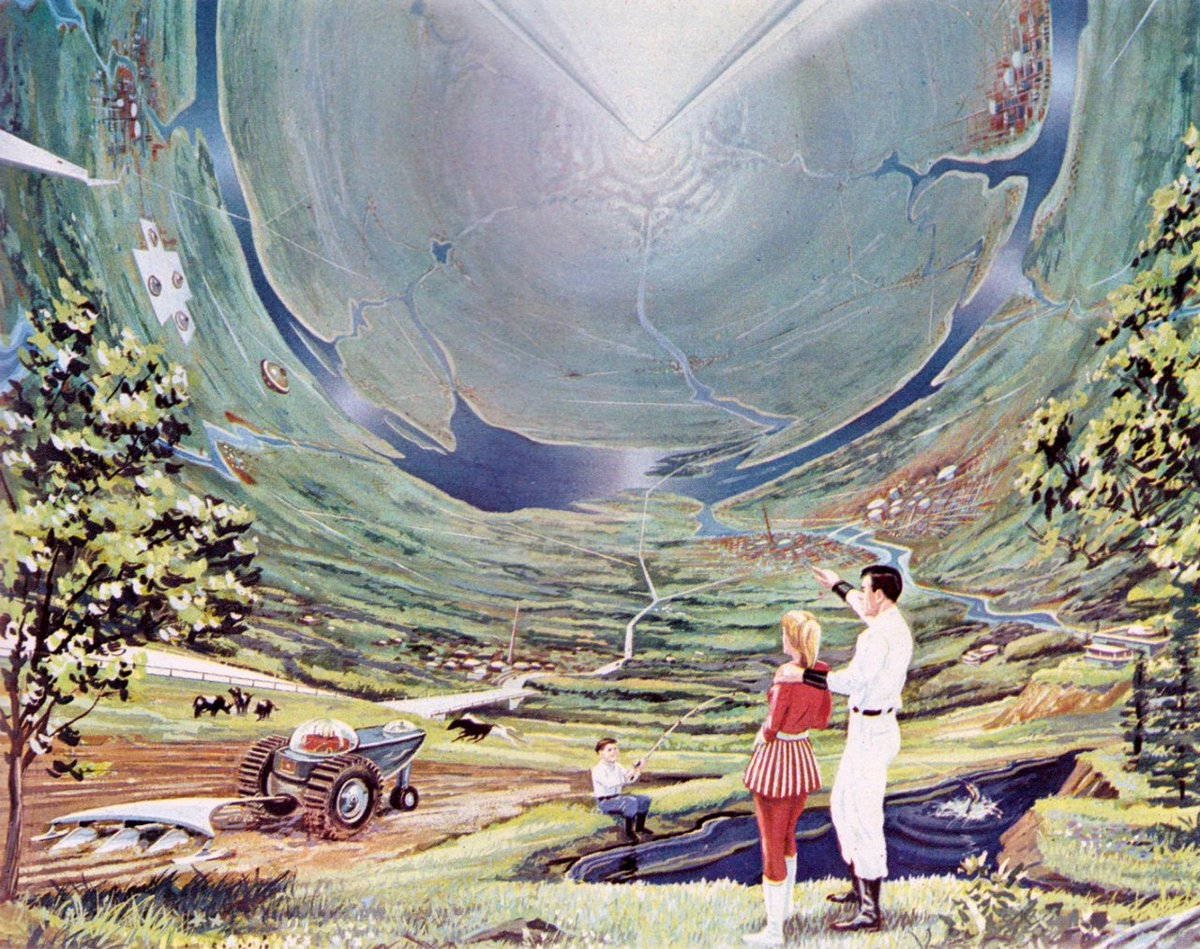

Americans born in the early 1960s may remember the book Beyond Tomorrow: The Next Fifty Years in Space (1965), with essays on hollow asteroids and electric rockets by the engineer and futurist Dandridge MacFarlan Cole. Each text was illustrated by the art director Roy Scarfo, whose romantic depictions of interplanetary sprawl preceded the better-known paintings by Don Davis, made for physicist Gerard O'Neil and his Yale University conference on space colonization a decade later. Davis's images of torus rings, Bernal spheres, and O'Neil cylinders carpeted with neo-suburban Americana resurfaced in 2019 when Blue Origin CEO Jeff Bezos (b. 1964) unveiled his vision for future human colonies in orbit around distant planets. Not only does this lineage expand the social and territorial logic of the post-war US to a potentially infinite scale, it takes its associated means of food production with it.

Food cultures in space tend towards legibility and orderliness. In science fiction, a world beyond scarcity is represented by the subatomic replicator in the Star Trek franchise, a utopian labour saving device that is the hopeful cousin to the ultra-processed sandwiches in 2001: A Space Odyssey or the energetic goo from The Matrix that boasts “everything the body needs.” In either case, a local axis of disgust and desire is translated to a new environment where it can feed contemporary anxieties and fears. When the context shifts to industry and government programs, emergent trends in food and agro-tech are faithfully incorporated (The Martian provides a rare moment of agricultural realism in film, though in service to verisimilitude only: you cannot detoxify regolith with shit).

In many ways, humans already live on Mars. Our awareness, extended via sensors and robotic arms, is busy cultivating, sampling, and turning over Martian soil. SpaceX’s plans for underground hydroponics and faceted glass domes soon return us to the least habitable settings on earth, where artificial biospheres like the Antarctic Eden ISS are researching food production for space. Yet even vertical farms, aquaponics, and fertiliser drones retain more than an echo of a food system bent towards cultural and economic will, and not the gastronomic possibilities of our planetary condition. The 2019 paper “Feeding One Million People on Mars” estimated the means by which a population of one million could sustain itself within 100 years, but the study was implicitly about environmental shifts closer to home. It noted key technologies including gene editing, cellular agriculture, and synthetic biology, farming methods that effectively resist our cultural imperatives because, in short, they are far more difficult to see.